Thinking beyond a conventional conception of time and its passage

Thinking beyond a conventional conception of time and its passage

I have been at Mount Allison a number of years and each fall, as the new academic year begins, I hold a contradictory sense about the movement of time. For just a little while, time seems to stand still as all is poised on the edge of perfection under blue skies: eager students, new opportunities, and all the freshness of a new beginning. On the other hand, we quickly plunge into the semester, and each year it seems to rush away faster and faster, leaving me breathless and wondering where the time has gone. As I write this, a week after Thanksgiving, I realize the beginning of term is already more than a month in the past, and we are one month away from Reading Week: The term is half over. I think I can hear the hands on my analogue clock whirring round; I wonder if inflation extends beyond economics; not only does a dollar not buy what it used to, an hour seems to go by faster than before.

The ancient Greeks had two words for time, and used them to distinguish between the routine passing of time and the special moments in time. Chronos, the first word, meant time that can be measured – in minutes and hours, days and weeks and even an academic year. We see this root in the English word chronological (denoting the movement of time, and time in the right order). On the other hand, kairos referred not to the quantity of time, but to its quality. Kairos refers to those special, mystical, wonderful moments that seem like they could last forever, but don’t. Kairos refers to those pieces of time when we feel fully alive, engaged, at peace, that all is well with our world.

We live, of course, in chronological time, measuring our days in hours and our term in weeks. On a grander scale, we measure our lives in weeks and in years. But we can also live in those moments of transcendent time. Chronological time shaped the lives of the ancient Hebrews through the seasons of the year, not simply as cycles of repeating time, but as movements forward on a linear trajectory. Likewise, the Christian tradition observes the church year beginning each December in Advent and continuing through cycles including Lent, Easter, Pentecost and back through what is referred to as Ordinary Time. However, it should be noted that the Biblical writers also encouraged people to live not just according to the passing of time, but to its celebration in those moments that create and re-create us, those moments that are not so ordinary, which we might or might not schedule, those moments when we suddenly realize we have grown a little, or fallen in love, or learned something new, or experienced something special, or perhaps in which we have just found some peace and calm. The author of Ecclesiastes writes that there is a time to every purpose under heaven (a time to be born, a time to plant, a time to laugh), and these are moments of kairos, time that is different and filled with meaning.

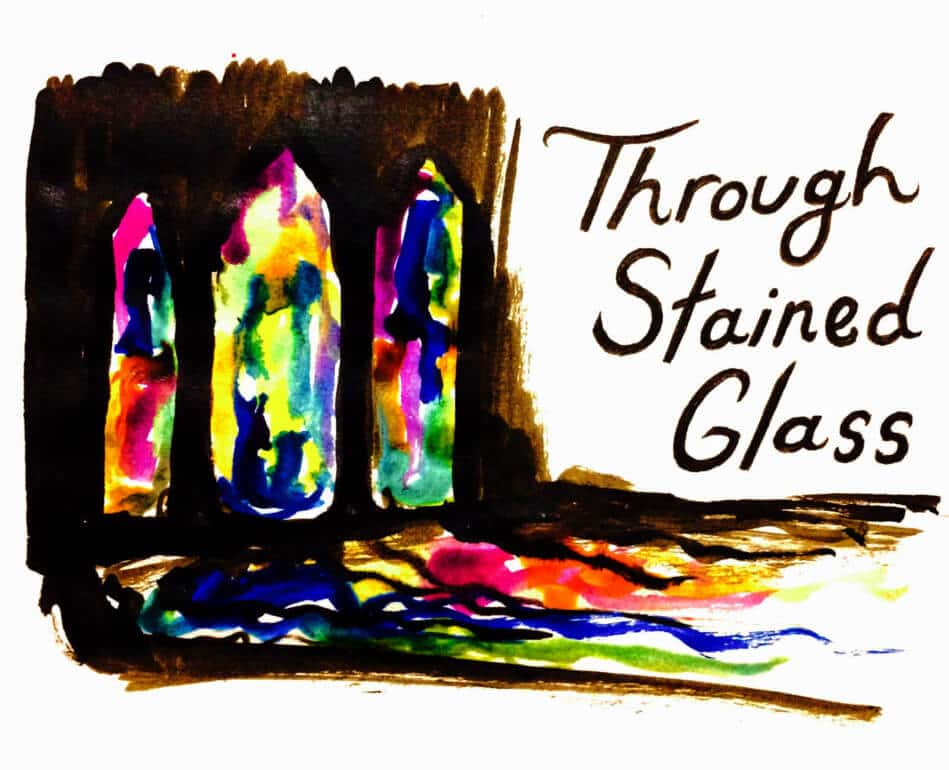

It is incumbent on us, who live in time measured by digital clocks and calendars, by schedules and deadlines, to seek out those times that are different, to pause and truly feel alive. For me, the experience of weekly worship is an attempt to capture the spirit of kairos – a time like no other, in which we come together and share in the word and worship, and open ourselves to the deep mysteries of life. Whatever our sense of religion or spirituality, it becomes more important in our fast-paced world to find those moments that make time stand still for just a little while; it is essential that we seek out and know that life can be perfect in those moments, even as we realize it is not always so through the passage of time, seen in the changing light through stained glass.