On May 2 and 3, Mount Allison hosted a series of panels and discussions entitled “Days of Action and Reflection” to review the university’s work toward indigenization and decolonization over the past year. The event, geared toward faculty members, allowed educators and administrators to reflect on the success of the Year of Indigenous Knowing and set goals for the Year of Indigenous Action, which began on May 1.

The event began with a talk by Chris Hachkowski, principal of Aboriginal Studies and assistant professor at the Schulich School of Education at Nipissing University on Monday night. Hachkowski highlighted the importance of evaluating the inherent Eurocentrism of postsecondary institutions, building relationships with Indigenous communities and re-evaluating the university’s definition of success to match that of Aboriginal communities.

While numerical measures can define success at the administrative levels of universities, they fail to resonate as meaningful measures of success to Aboriginal community members, according to a series of conversations facilitated by Hachkowski and other researchers at Nipissing.

The results of their study indicate that administration and faculty members at universities should create learning environments that emphasize community building and the individual’s journey of identity building should they seek to indigenize.

The following day, over 50 faculty members gathered in Tweedie Hall to share their experiences with the University’s attempts at indigenization over the past year. Planning for the event began in late fall of 2016. According to Jeff Ollerhead, provost and vice-president academic and research, organizers wanted the event to occur between the end of winter exams and before convocation in an effort to draw the largest number of faculty members. The lack of student involvement as a consequence of the timing was a weakness of the event identified by VP International and Student Affairs Kim Meade.

“Obviously, the event was really geared toward faculty, and from the participation you can tell the timing worked,” Meade said, referencing the faculty high turnout.

Maritza Fariña, a Spanish professor who also spoke on one of the event’s panels, was impressed with the number of faculty in attendance. “It’s very uncomfortable to talk about decolonization of knowledge….When something makes you uncomfortable, it’s easier not to face it,” she said.

Throughout the course of the event, many discussions centered around the issues inherent in decolonizing a space like a university, which has historically relied on colonial knowledge structures.

Geography professor and event panelist Leslie Kern believes there is a paradox in decolonizing the university. “Is it even possible to do that in a way that would meaningfully reflect what decolonization means to Indigenous people?…I’m not sure that we would recognize [this institution] if decolonization was truly the end goal,” she said.

Fariña emphasized that the knowledge upon which the university is founded comes from the perspective of the colonizer, and that the process of decolonizing this knowledge system begins with learning from the colonized. “To decolonize the knowledge at a higher education institution, we will have to walk a very, very long and uncomfortable…road,” she said.

Sociology professor and panelist Lori Ann Roness spoke about the limitations of decolonizing through curriculum changes and the need to expand our understanding of indigenization. “Indigenous students don’t need to take a course on being oppressed,” she said. “And while I can’t speak for Indigenous students or people, I imagine that a safe place means a place where they feel welcome and where they see themselves in all aspects of the institution.”

Andrea Beverley, a Canadian studies and English professor, acknowledged the discomfort that many event participants felt talking about indigenization in a space where most individuals are highly privileged. “We might feel, justifiably, that talking about indigenization at the institution is a fad, that it’s PR, that we’re just heading toward tokenism, that we’re always calling on the same students,” she said. “We might think sometimes that academia and Canada might be irredeemable project[s] because they are so fraught and so problematic. Why can we expect change when we haven’t seen substantial change following many other moments of resistance and calls to action?”

However, Beverley pointed out that the willingness of faculty to engage in this discussion is indicative of the possibility of change. “Change is possible. I’ve seen change. This day we’re having right now wouldn’t have happened when I came here four years ago,” she said.

Several speakers highlighted the necessity of hiring Indigenous faculty in the ongoing process of indigenization. Emma Hassencahl, a Maliseet fine arts student and Mt. A’s Indigenous Affairs intern, said that although she is skeptical of the project of indigenization within the University, she believes that hiring Indigenous professors is an important step toward making campuses more welcoming to Indigenous students. “Even if I don’t personally understand where indigenization is going, I think that it’s something we should keep striving toward to ensure that Indigenous students feel comfortable and safe,” she said.

Some participants and panelists felt that continually asking Indigenous people for their participation in a project of decolonization could overlook their interests, particularly if the project is for the sake of non-Indigenous people only. “We keep saying that it’s important to have the participation of Indigenous peoples in the project of decolonization, yet we also have to ask ourselves why Indigenous people want to be involved in the project of decolonizing Mt. A,” Kern said. “Why should people invest their time, knowledge, emotional labour and so on into decolonizing a colonial institution? What do we have to offer in return?”

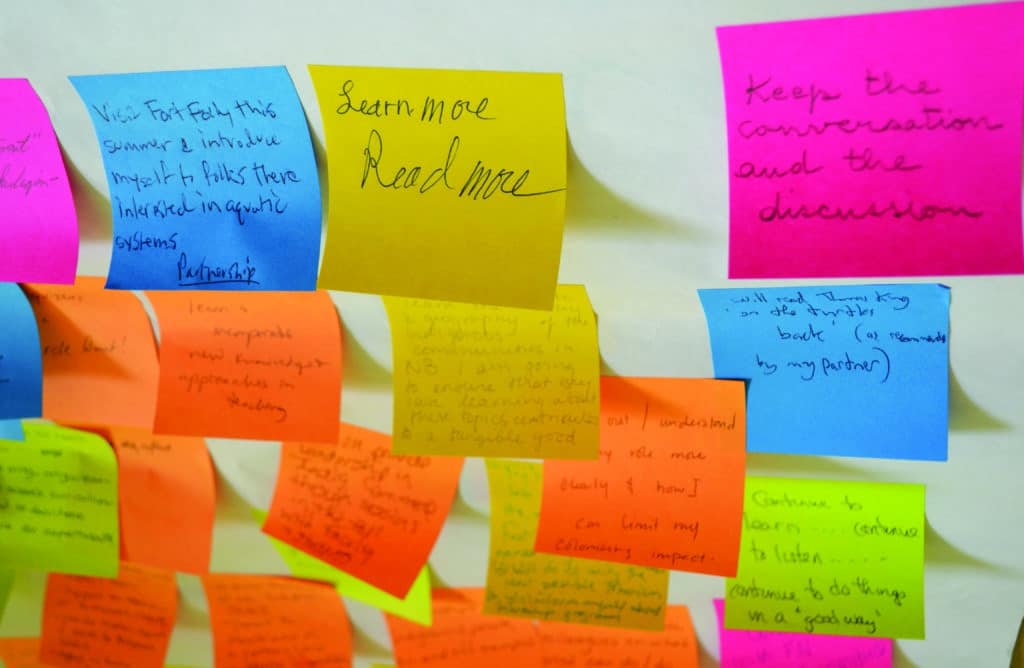

By the end of the second day, many faculty seemed hopeful about the ideas and goals that arose throughout the discussions.

Fariña believes that the event showcased “the first steps to something that will come.” She highlighted that the work of decolonization should not be limited to faculty, and that students should commit themselves to asking questions. “It has to come from [students],” she said.

As potential steps forward, Ollerhead referenced institutionalizing a fund for field trips, creating an Indigenous Advisory Circle composed of students and community members and organizing a similar event of reflection for students in the fall. In addition, Ollerhead mentioned an Indigenous hire is currently high on the agenda of the University Planning Committee.

The prospect of decolonizing an institution steeped in colonial structures and values is undeniably a complicated and long-term project, but one that many faculty members expressed an eagerness and desire to pursue. “It’s about doing something every day,” Fariña said.

Martiza Fariña recommended that those interested in the discussion surrounding indigenization and decolonization read Chief Dan George’s “A Lament for Confederation.”